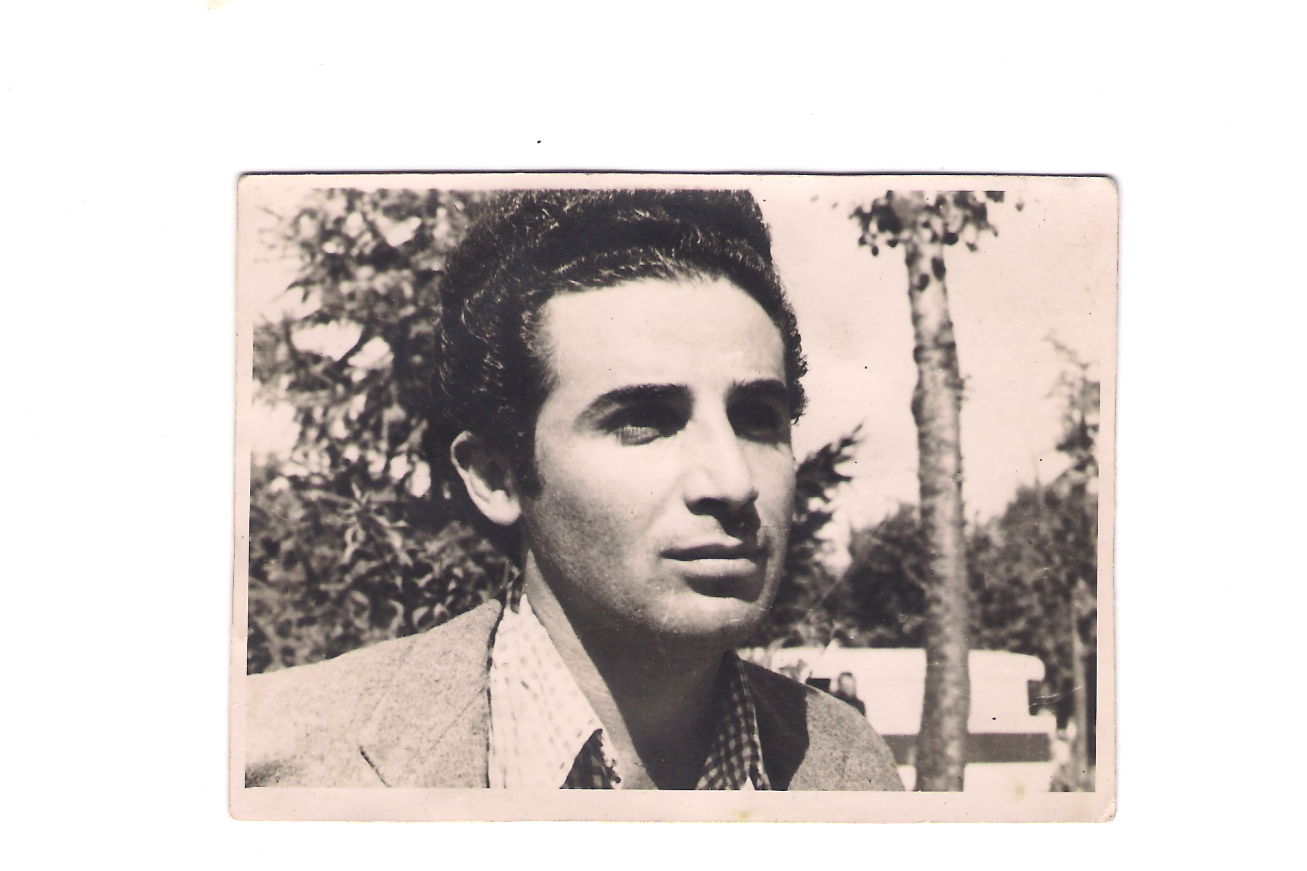

Ervant Nicogosian

6 December 1928 — 26 May 2014

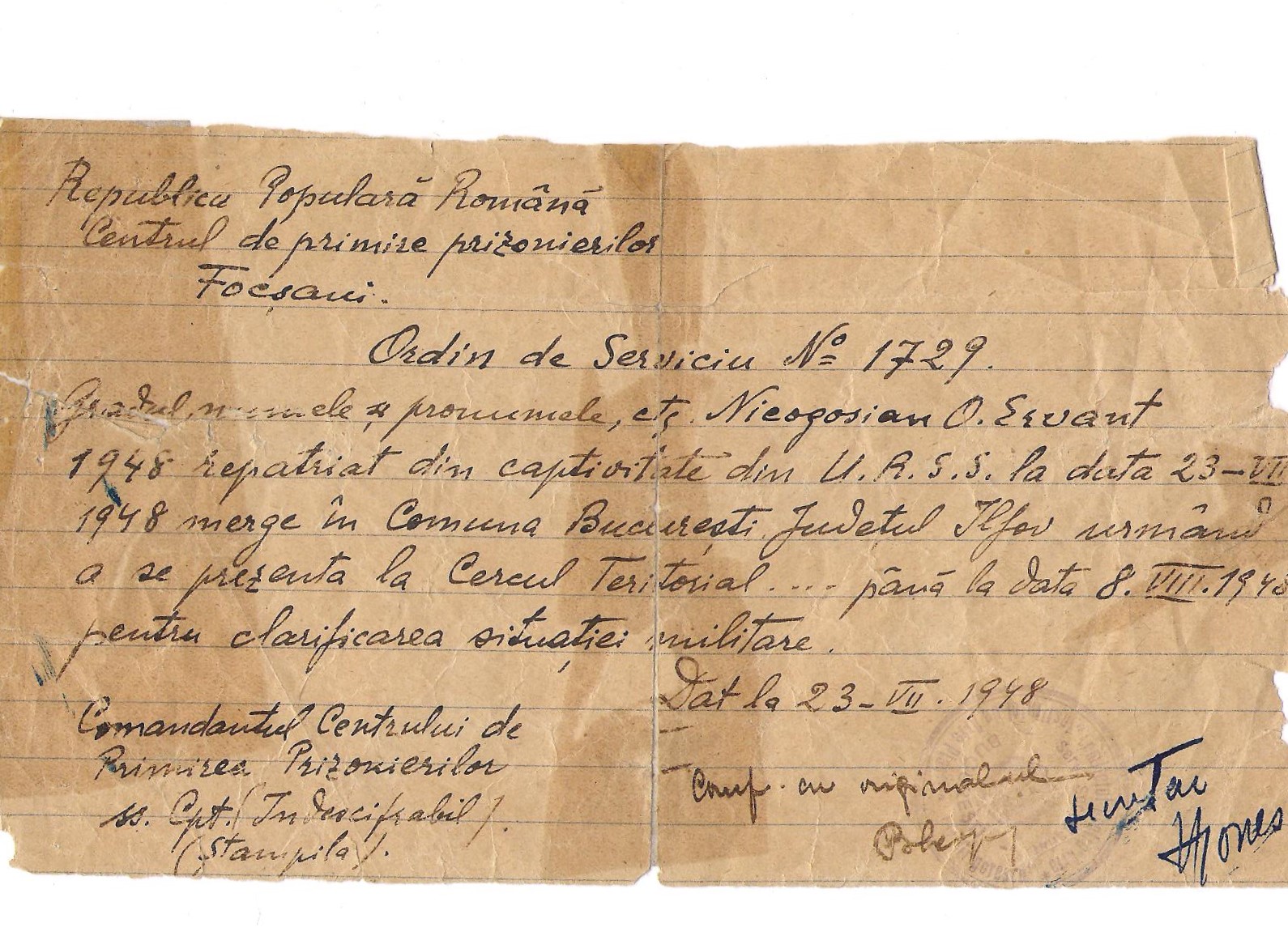

Born in Odessa on the 6th of december 1928, Ervant Nicogosian was deported together with his family to the concentration camps in the Soviet Union (between 1941-1948), passing through the forced labour camps from: Oranke, Aktiubinsk, Karaganda-Spask, Kocuzec, Akiatan.

He later confessed that until the age of twenty-two, he lived in the concentration camps in Kazakhstan together with his parents, the two sisters and his older brother. “The first concentration camp I arrived was Oranke in the middle of the summer. It was a former monastery, situated on a huge meadow, surrounded by birch trees, very close to the city named Gorki, Nizhny Novgorod nowadays. Inside it, Russians transformed it into a jail, where after a journey of 42 days we were thrown.” Ervant Nicogosian writes in “Confessions’ ‘ partially published in the Ararat magazine. The biography of this artist contains the excruciating hardships of a brutal deportation, childhood joys, fear, light, panic, hunger, the cold in the Siberian steppe, illness, death, and above all the hope that someday they will get out of the inferno of the “Gulag Archipelago”. Between 1948-1954 he studied at Nicolae Grigorescu fine arts Institute in Bucharest, at the class of professor Camil Ressu, where he had as colleague, among others, Paul Gherasim that became his lifetime friend.

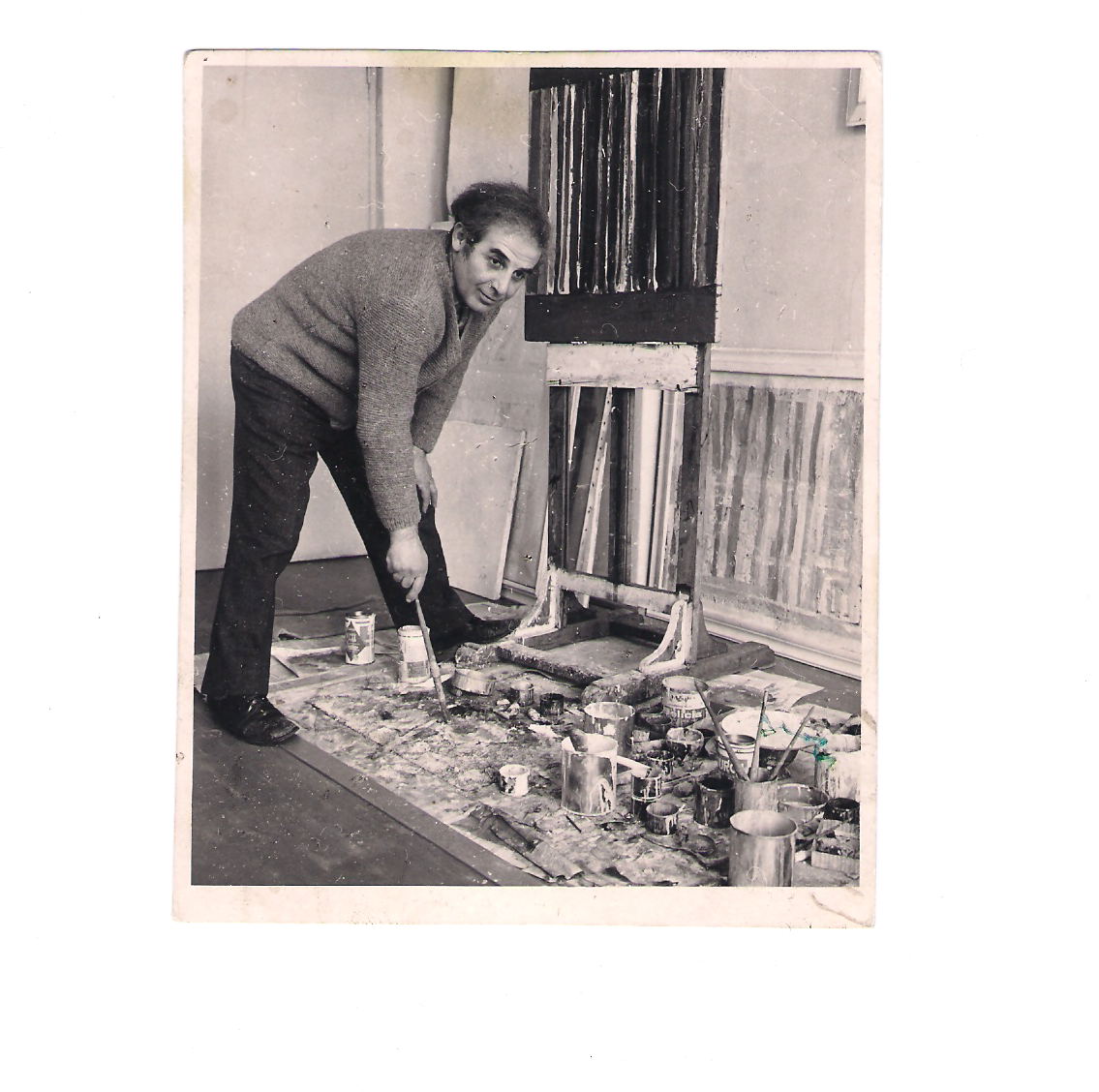

Right after graduation he becomes member of the Visual Artists Union, Painting department. But his artistic creation was not limited only at painting, since Ervant Nicogosian created monumental art as well among his creations in this line we can enumerate: the marble pavement from Pangratti studio, ceramic mosaic from the Bărăganul village, Brăila county, stone and marble mosaic depicting a famous Middle Age Battle on Râmnicu Vâlcea National Archive building and the Murano glass mosaic from the Sâmbăta de Sus monastery.

During his lifetime, Nicogosian had countless exhibits in Romania like in:

– 1966 – Bucharest, Simeza Gallery

– 1970 – Bucharest, Orizont Gallery

– 1974 – Bucharest, Apollo Gallery

– 1975 – Bucharest, Simeza Gallery

– 1988 – Bucharest, Simeza Gallery

– 1988 – Bucharest, Armenian Church

– 1998 – Bucharest, Armenian Church

– 2002 – Bucharest, Curtea Veche Gallery

– 2006- Bucharest, Senso Gallery

– 2009- Bucharest, Simeza Gallery

He also exhibits abroad in Prague, Warsaw, Geneva, Prilep, Paris, Metz. Many of his artworks are in private collections from Romania and foreign countries but also in museums from Romania and Armenia.

Unfortunately, in his last years the artist faced a terrible illness. He lost his eyesight; but even so he didn’t give up painting and with the help of a fellow artist and of his daughter he pursued his love for art.

Ervant Nicogosian dies at 26th of May 2014 in Bucharest.

ERVANT NICOGOSIAN – interview realized in 2006 for Revista 22

“My dream was, during Gulag time, the windows”

Mr Ervant Nicogosian, your artistic biography, and in fact your biography in general is very special. You mentioned in a previous interview: “First thing I remember when I am being asked how was my childhood is distress” …

Yes, indeed! I had a very interesting childhood. One like the kids today don’t have, when they are spoiled with oranges, chocolate, toys. I was born in the Soviet Gulag, in Odessa, a city with a very peculiar population, underground and very diverse, like of a big cosmopolite city. There were Greeks, Jewish, Romanians, Armenians, Russians, Turks. My parents considered themselves Romanians. Armenians from Romania. They left Romania during the First World War, around 1916-1917 and they establish in Odessa. A very interesting city indeed Odessa! A city of pickpockets, of prostitutes, everything what was negative. When I was a kid I liked being part of gangs. I liked to mix with them.

What attracted you at these gangs?

My temperament, most likely. My bigger brother and my two sisters were not like me; they were really serious. They preferred to stay out of trouble. But I was fascinated with these gangs, with this underground world. Odessa is famous for its hooligans. It was something that I can’t describe. I was simply attracted.

And about this congenial Odessa hooligans can you tell us a story you witnessed yourself?

For example, I remember there were a lot of pickpockets’ gangs and they even had some sort of a school for pickpockets. Yes, a real school. Odessa is also famous for its catacombs. And a lot of them were used for smuggling since ancient times. Brief, the city is built on these underground galleries. And in here, in underground those “schools” I mentioned before were organized. The pickpockets from Odessa were the most skilled and most famous from the entire Soviet Russia. They were so quick that you didn’t realized you were being robbed. A Russian expression illustrates best this kind of action, they were so quick that they stole your shoe sole while you were walking.

I think that these characters resemble a bit with the characters from Dickens stories…

Of course. When I first went in the underground, I’ve seen how they were taught to steal unseen, how they gain their skills. The master placed a dry tree and hang in it all sort of small objects; among those objects small bells were tied. The pupil had to take a certain object without disturbing the bells. If the bell rang you failed. A lot of them succeeded after several trials.

Have you succeeded?

Myself? I didn’t try since I was really afraid that I will fail. I just took part and witnessed the lesson. I really liked those guys! I will never forget how they were dressed: berets with large brims, shorts or cropped pants, just like the kids in that old American movie, Once upon a time in America.

And is there any connection between thse childhood adventure and yoir passion for painting?

Oh, i was really passionate about painting and they were definitely extremely picturesque.

Have you tried to draw them?

…. You cannot imagine how funny those people were when they hang themselves like bunches on the countless metal sticks from Odessa. The city was full of old houses with metal sticks around them. And when the gang meet some were perched on the metal bars and others were sitting on the ground. I stayed next to the ones on the ground. I was the youngest of them. The biggest was twenty something while the youngest was fourteen. I barely turned eleven at that time but they accepted me. They told me: come and sit with us! Watch and learn! I was just sitting and smoking with them There is where I started to smoke or to sing prison songs. As an aside: Odessa was at that time in the proletKult era and the whole city was full with workers clubs where young people were forced to go and learn from political commissars the so-called patriotic songs. I went to those clubs since I had this revolutionary spirit, an anticapitalist since I was a boy at eleven. Inside we were singing patriotic songs but once outside we continued with prison songs. But songs from anti-Soviet prisoners. Odessa had at that time thirty-eight prisons and most of them were filled with political convicts, especially intellectuals.All those things I’ve told you about the mottled and weird population of Odessa inspired me. I was making drawings.

Have you kept drawings from that period?

No, definitely no! Well, they took us in ’41 and took us to the forced labour camp! Us – my family, my father, my mother, my brothers – we kept Romanian citizenship. Other, in order to avoid deportation and not to be thrown in prison like us, changed their status, becoming soviet citizens. We didn’t want. My uncle, mom’s brother became soviet citizen. And he remained in Odessa, he wasn’t deported. They took us in ’41, during the war, before Romanian occupation of Odessa. Since we were Romanian citizens, we were considered enemies of the Russians. We were simply taken in mid-day, on twenty something of July. A big black van came with 8 comrades, 6 from soviet militia and 2 apparatchiks and throw us from our home, one by one with only one bag per person. A lot of people gathered when they saw the black van. We were 6 people: father, mother and four children. We weren’t allowed to take more than one bag and my parents preferred to put in the luggage, books mostly. So, my drawings from that period were lost.

We spent in the soviet Gulag seven and a half years and we passed through five forced labour camps. I went out from there at 21 years old, in ’48 when we were repatriated as Romanian citizens.

What was your first labor camp in 41?

In Oranke. Some sixty kilometers from a city called Gorki used to be a monastery and its name was Oranke. The Bolsheviks made a prison out of the monastery. I remember the church monastery had a typical Russian architecture, very beautiful, with five round towers. And they destroyed it. They imprisoned common law prisoners and political prisoners too. Inside the church, next to all the walls there were bunk beds, some seven-floor high, called “nare” touching the ceiling of the towers.

I dont think there were any icons left…

Icons? No way! It was only a prison there. On the walls there were fragments of the old frescoes. All the monks had been imprisoned there together with the rest of us. And people were dyeing daily and their bodies were thrown in the Volga. When I first entered the church and saw all those bunk beds, I thought they were trying to restore the frescoes. I must tell you that some of those frescoes were painted by grand masters from the Rubliov school or the school of Teofan the Greek. Extremely beautiful paintings. Over them, all kind of inscriptions. The prisoners before us wrote on those walls all kind of things. So, entering the church for the first time I thought that we’ll help restore it, probably. When one of the guardians came and assigned us our place; there were seven rows of bed bunks with only one meter and half space between them. We stayed just for a short time here and they sent us away quite quickly.

The labor camps, in Oranke and in the other four places we’ve been through – all kind of nationalities: Estonians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Danish, Hungarians, Polish. AT the beginning the Romanians were a small group, but after ’44, after the Soviets reoccupied Basarabia, a lot of Romanians were sent to the Gulag too.

I know my question may sound redundant, but I will address it: how was life in the forced labor camp, how did you survive there? Please give us some details about the horrendous life that you had there!

How could one person live in the Gulag? People were dying. There were three main diseases that could cause you death: pellagra, malaria and the dysentery. People were getting sick due to the bad food and physical exhaustion. They served us a bit of stale millet, some sort of a black porridge made with colza oil and a strange soup, more of a liquid out of sour fish, mostly bones. This was our daily food. Our family resisted because we were kind of used with the misery starting from Odessa. But those coming from other countries like Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Denmark or Belgium they didn’t had a chance to support this type of nourishment. And they were dying of pellagra. Malaria started when they moved us to Kazakhstan, were we’ve been in four forced labor camps: Aktiubinsk, Karaganda-Spask, Cocuzec, Akciatan. In Oranke we stayed less then a year. Because the front line was approaching, the forced labor camp with its beautiful church had to be moved further. They took us from Oranke in the middle of the winter and took us to Aktiubinsk, the worse labor camp. During the winter the temperature was 40 below Celsius while during summer time plus 40 Celsius degrees. Hypercontinental climate. Here the worse dangers were malaria and dysentery. They simply swelling. My father was swollen; I was staying with my brother during night time placing hot bricks on his feet. We survived. In Karaganda I was working with my brother at the painting workshop from the camp and we were able to steal a bit of the oil used there for colors so we could have for frying the potatoes.

Since you mentioned painting, when and how did you start painting?

Me – why should i play the modest – I think I was talented since a very early age. My brother had also talent but he was less imaginative.

Who guided you to painting, at the beginning when you were a child?

My father tried to guide me, since he was quite talented. He would like to dedicate himself to art, but my grandfather, a wealthy merchant from Brăila, asked him to be an engineer. My father, the only left child from twelve born, pleased him, but he remained his entire life passionate about art. He also like to sing. When we were in Odessa, a lot of Romanian family friends came (refugees also from the first world war) because my father had musical instruments and they were singing together. When my father saw that I have artistic talent, took me to a drawing teacher in Odessa, an old Jewish person, Ginsburg, who had a private drawing school. I was only ten years old. At that school I learned how to draw like at a Fine Arts Academy, after famous busts: Laokoon, Hera, Venus and others. Mister Ginsburg was really talented and received me and my brother even if we were the youngest from his school.

How did you manage to draw in the labor camp?

In the first two labor camps I couldn’t do anything. In Aktiubinsk, as I told you, we had to endure the Siberian cold and an atrocious misery. They took us to Karaganda after, where we stayed up to ’48. Not in the city, of course. Outside the city, some one hundred kilometers distance. All you could see was steppe, thousands and thousands of kilometers of steppe. When we arrived, they told us that they could live us there without fencing the labor camp, since you don’t have where to run. Still, there were four rows of barbed wire and of course the “owls”. We call “owls” some sort of observation points where the sentinels used to stay. In Karaganda-Spask after two years they organized some sort of artisans’ factory. Soviets came and selected people who knew different things: a few weavers, some three puppeteers, and among other sculptures and painters. A professor came to the camp, Iura Ivanovski, a pretty endowed painter and he started there a painting workshop.

What were your theme for painting at that time?

In the beginning, this man, Ivanovski, tested us, like some sort of exam. There were 6 of us aspiring to become painters in the camp. Ivanovski made a portrait of Lenin, in front of us. He painted as the Russian paints: good. Then he turned to me and said: Kid, if you can make a portrait like this one you can work here in the painting workshop. And everyone had to pass the same exam. I watched him while painting. Three days in a row I spent in the workshop watching him working other orders. And I said to myself: I can do this! And I did it. And Ivanovski loved it even more then his own painting. That’s how I started. The teacher, choose me and my brother and other three Polish as painters and three sculptures and those who were making the colors some Japanese war prisoners. That’s when I started to paint in oil. Before the Gulag, in the school from Odessa of Mr Ginsburg I only learn to draw after sculptures. In Karaganda-Spask I only made reproductions from Russian painters like Levitanov, Șișkin, Perov. Those reproductions were in high demand.

And where were taken those paintings made in the Gulag?

They remained in the camp, of course.

Were they exhibited somewhere?

No way! Where to be exhibited? The commanders of the labor camp came and pick them.

Where did they take them?

They put them in their homes. I painted for the soviet chiefs of the labor camp. But it was a good thing that Ivanovski came; he saved us from a very hard work. Unfortunately, only my two sisters had to work in the camp. And another good thing happens: a Jewish origin apparatchik, Misha Oigenstein, started a ten-class school, following the soviet model. He took from the coal mines a great number of valuable people: professors, engineers, doctors, scientists and brought them as teachers at this camp school. Most of them were of German citizens, that came in Russia in ’36-’38 when Molotov and Stalin had good relations with Germany. When the war started they were brought into forced labor camps and asked to do humiliating things.

I have a great curiosity: could people be still religious despite the terrible conditions from Gulag? Did they still believe in God?

To believe in God in those conditions you should have been educated in the spirit of faith. Somehow, I had received from my parents in Odessa, some religious education. But in those times mattered the school, where they didn’t teach you to love God. By the contrary, they teach you that if you meet a priest, to swear him. Especially if you saw him begging – because since they didn’t had jobs, they started to beg on the streets. The churches were dynamited. Odessa used to have a lot of synagogues too and only a few resisted. I remember how a big cathedral was blown in the air. We stayed at some three kilometers from it and we sticked on the window big crosses of paper and even saw our windows broke due to the explosion. That was the Soviet Union, that was the Bolshevik power. They were teaching us not to go to church. If you were going, you were risking to be betrayed by other colleagues.

What were you thinking? What were your hopes during Gulag time?

I wasn’t hoping for anything. I grew up in the labor camp, I lived my adolescence there. I saw people getting old and dying there. I thought I will die too there. I never thought I will be free again. When we arrived at the repatriation camp from Focșani I acted like a lion that just escaped from a cage. Because I lived so many years among so many strange people, I acted extremely detached. I didn’t have any respect, any restraints. Once arrived in Romania, I went straight to the Ministry of Education.

What was your request?

To be admitted at the Fine Arts Academy.

When have you enrolled? In 1948?

Yes, in ’48. When we returned to Romania, we stayed a couple of months with one of my cousins and when she saw me painting, she insisted I should go to Fine Arts Institute.

What teachers did you had there?

I had teachers, like nowadays you can’t find any longer. Dărăscu, Negrea for sculpture (since I also done a year of sculpture), Medrea, Steriade. Ressu was my teacher since the second year up to the final one. A great teacher Camil Ressu! A person who gave you notions about drawing, on how to construct a figure, a person, a composition, to organize the surface of the canvas, to better distribute the elements of painting, thinking and not just working randomly. Ressu had an authentic realism, not a naturalist like Baron von Loewendhal, who taught you to draw all the face lines. Ressu taught you the essence of a thing, of an object, of a figure. The essence! He was teaching you the ABC! He made you paint and in the same time to use the proper color, even if he wasn’t a colorist par excellence. Those five tons that he put on his palette, were base tones; essence was everything for him. He urged you to paint using your synthesis capacity; he asked you to better understand everything, not to be superficial with your artwork. Ressu was not like the rest of the teachers. He came, sat in front of the easel and around him the students gathered, watching him painting. During his classes, student from the entire Institute came; of course, those who loved Ressu’s work.

What have you done after graduation from the Fine Arts Academy?

I married right after graduation and it was quite hard, of course, since we were passing through a dark period from ’54 to ’64. The proletcultism period, when you had to paint according to the communist slogans. If I refused to do so, I wouldn’t get any money for my artworks. And I needed the money. In ’55 my daughter was born. My wife couldn’t work anymore as a juridical counsellor. So, I had to paint big propaganda panels or work protection panels from the factories. I also painted for the Health Ministry. I made a lot of kitsch work; I was forced to prostitute myself through my art. It was a disastrous period. I didn’t paint the dignitaries of the day, like Dej or Maurer like others. But I made propaganda panels. That was the only way you could survive back in those days. Until ’63 I was constantly sent all over Romania’s factories for documentation. An age of darkness, a truly nasty period! I started to paint industrial artworks starting with ’63. But these were of a better quality. For example, while painting ships from Galați Harbour, i started to create for real. I was inspired by Galați landscape and especially by its luminosity. I made paintings depicting shipyards up to the beginning of the ‘70s. And after that I painted as I wanted too. There were paintings where I could find myself in. I started a new phase dedicated to windows and white tones. Those are related intimately to my Gulag life. My dream was in the labor camp, the windows. Liberty, liberty was all I wanted. I wanted to see windows opening. This stage of artistic creation lasted till mid ‘70s. Then I started to work on “The Old Princely Court” series. The windows from my atelier were orientated towards these impressive ruins, that I’ve watched daily and I learned how to love those walls more and more. Its not that I only loved that Princely Court, but I realized that she is more then an inspiration, it something that belongs to me. That I rediscovered myself in there perfectly. I am an unsophisticated, atavistic person by excellence.

” The value of Nicogosian’s artwork comes from his power, the same power of a man that stood up with dignity and faith, over the years, both the communist terror and the Gulag’s atrocities, filling with color life sorrows.” Said the great artist and lifetime friend Paul Gherasim, during the vernissage of the important retrospective organized by Senso gallery in 2006. “This kind of exhibit, like the one from Senso Gallery, is meant to crown a lifetime work of this fighter and transform it into a model for all of us”.

Paul Gherasim, painter

How many paintings did you worked on your entire life?

“I painted quite a lot over three hundred paintings. Some are in Romania in different museums or private collections, other like half of them is abroad.”

Cam câte tablouri ați pictat toată viața?

“Am pictat foarte mult peste trei sute de tablouri. Unele sunt în țară, prin muzee sau colecții particulare, altele, cam jumătate, sunt în străinătate.”

Learn first about future events

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.